| |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||

Massive famines followed. Violence and anarchy broke out up and down the Nile. The royal government in Memphis lost control of the nation and centralized record-keeping disappeared. Egypt fell into a dark age. Why the failure of the flood? Global climate cooling resulted in decades of reduced rainfall in central Africa. New evidence indicates that the global effect was due to a massive meteor strike at this time. (Other ancient civilizations - the Akkadian and Indus for example - collapsed at this time also.) |

|

||||||

| The nomarchs struggled to control, irrigate and feed their own provinces. Some were more successful than others. While some nomarchs still officially recognized the remnant of the Old Kingdom in Memphis and the kings of the 7th and 8th Dynasties, others proclaimed themselves kings in their own right. Around 2150 BC, the nomarchs of Herakleopolis - descended from Neferkare (2150? BC) - successfully proclaimed their own dynasties, the 9th and 10th, and claimed royal prerogatives. Their influence extended as far south as the nomes of Abydos and Koptos. Here they were challenged by the growing power of the nomarchs of Thebes in Upper Egypt, descended from Antef I Inyotef (2100s? BC), who founded the 11th Dynasty. Other less-powerful nomarchs, while having some degree of independence, attached themselves to either the Heracleopolitan or the Theban dynasties. A clash between the two rival dynasties was inevitable.

They waged their conflict first with diplomacy and then with armies,

plunging at least part of the country into a civil war. The final victory

of the Theban 11th Dynasty, led by Mentuhotep II (2055-2004 BC), marked

the beginning of a new era of unity and prosperity: the Middle

Kingdom. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

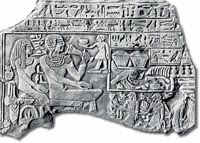

On the other hand, the 1st Intermediate Period marks the spread of "Pharaonic Culture" throughout the country. During the Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom, this 'royal culture' had been limited to the court and the aristocracy surrounding it. During the 6th, 7th and 8th Dynasties, as nomarchs up and down the Nile gained increasing power, they began to adopt the style, fashion and etiquette of the royal court in Memphis. This brought the images and trappings of Egyptian royalty to the people at large, and ensured their survival into the future.

|

|||||||

Home | Nile Valley | Dynasties | Wealth | Divinity | Temples | Hieroglyphs | Mysteries

|

|||||||