|

The ancient Egyptian sculptor and painter worked to promote immortality.

They had a religious and funerary purpose - to keep the subjects of

their art 'alive' - just like mummification and inscribed hieroglyphic

names.

Originally artisans served only the pharaoh, but with the dissemination

of power in the 1st Intermediate Period, they began to portray nobles,

officials and their families as well.

Craftsmanship varied widely throughout Egypt, and dynasty by dynasty.

The better artists gravitated to the capital, of course, where wealth

and power resided. The provinces generally had the less-gifted artists.

Periods of stability and proseperity allowed for higher quality.

They produced statuary, reliefs and paintings.

We know the identity of some Egyptian artists, but for the most part

their identity is unknown.

|

|

Although artists were not generally

viewed as 'special geniuses' with gifts above normal humankind, excellence

was definitely recognized and rewarded.

Often Egyptian artists worked in workshops and probably divided the

labor according to skill and experience. Otherwise they worked in the

temples or tombs, decorating virtually every exposed wall and ceiling.

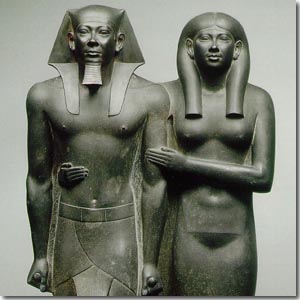

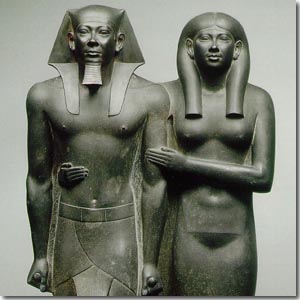

Statues of pharaohs represented more than just the man. They embodied

the idea of divine kingship. They were generally carved from harder

material than statues of ordinary mortals, carved for eternity. Seemingly,

the artists tried to express how the pharaoh wanted to be seen and remembered

- or at least that is how we interpret it:

Sometimes a King's servant received a funerary statue from his master,

but many of the richer elite could afford to pay by themselves.

The ancient Egyptian sculptor most famous today is Thutmose, who had

an atelier at Akhetaten and created many works in the innovative Amarna

style, and we know of Maya, a late 18th dynasty scribe and painter living

at Deir el Medine, because he also decorated his own tomb.

Thutmose was part of an ancient tradition of humanizing statues. An

unknown 4th dynasty sculptor created Prince Ankh-haf's likeness, another

Ka-aper's a few generations later, or a third Amenemhet III's during

the 12th dynasty. While many statues are idealized, it seems that quite

a few of the ancient Egyptian artists attempted to render their subjects

as faithfully as they could.

The Opening of the Mouth ceremony was performed on statues just as it

was on the mummy itself, animating them and enabling them to use their

senses.

ARTISTIC CHARACTERISTICS & CONVENTIONS

Statuary, reliefs and paintings:

- Resemblance to the depicted person was not necessary. Hieroglyphic

inscriptions usually identified the subject. Resemblance was more

often attempted in statuary than in reliefs, and more often with royalty.

- Most Egyptian images show youth, health and prosperity. Sickness,

disfigurements and old age are rarely shown.

- Servants are depicted smaller than their masters, wives usually

smaller than husbands, and children much smaller than all.

- Men most often painted red (ochre) and women pale yellow.

Statues only:

- The classical Egyptian posture faces straight ahead, whether standing,

pacing, sitting or kneeling.

- The faces are idealized and often individual and recognizable.

- Position of the body parts, though stiff, are natural and size-relative.

- The arms are held by the sides when standing and resting on the

thighs when sitting. Women sometimes hold or hug the man.

- Children portrayed proportionally as 'little adults'.

- Figures are rarely portrayed in the nude, though the women often

wear 'clingy' and revealing sheer linen.

- In block statues the body of the squatting person is turned into

a block of stone, the vertical sides of which are often inscribed.

Only the head receives realistic treatment.

- Statues were made of clay, wood, copper, bronze, ivory, many kinds

of stone, or plaster and paint. Gesso was often used to hide defects

in wooden and stone statues.

- Anthropoid sarcophagi (from the Middle Kingdom onwards) were at

first made of wood, later increasingly of stone. They show little

individualization.

- Funerary masks were generally made of painted carton and in the

case of pharaohs, of gold.

Reliefs and Paintings:

- To show all features, the body was portrayed as a collection of

body parts seen from different perspectives.

- Heads full-turned right or left, often facing a divinity, and therefore

seen in profile. The eye is always shown in full frontal view, not

as disconcerting to us who grew up with cubist pictures as it was

to the first Europeans to see this.

- Shoulders have a frontal view, sometimes causing awkward depictions

of arms when both stretched forward.

- Breasts are shown in profile.

- The lower body is shown in profile and often striding.

- Limbs, hands and feet (until the Amarna

Period) the same 'handedness' or perhaps rather no handedness

at all.

Paintings only:

- Stereotypical, even cartoonish treatment of contours.

- Personalization is through inscription instead of likeness.

- Roman-style drawings after the end of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. More

lifelike, but still often formulaic and repetitive.

|

|